Management of congenital complete atrioventricular block in a 3-year-old boy in natural history in a tertiary centre: a case report

Case presentation

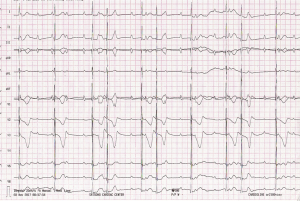

A 3-year-old boy was referred by a cardiologist from a clinic in Douala for management of complete atrioventricular block. The condition was suspected 2 years prior to referral by a pediatrician because of severe bradycardia. The child was referred for cardiological evaluation but because of lack of finances the family was forced to postpone the appointment many times. The cardiology consult was finally done 1 year prior to referral. Following clinical examination, both an electrocardiogram and echocardiogram was performed. The electrocardiogram confirmed complete atrioventricular block (Figure 1), the echocardiogram was normal without evidence of structural congenital heart disease. The patient was then referred to the cardiac centre Shisong for the pace maker implantation.

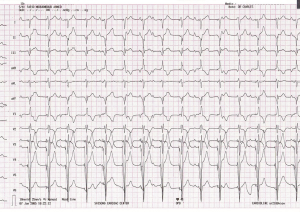

The history was remarkable for fatigue on mild exertion resulting in failure of the child to keep up playing with his mates. On arrival in the cardiac centre, the diagnosis was confirmed and the procedure was planned. Because of financial limitations, it took another 6 more months for the family to obtain the financial resources required for the procedure. Eventually a single chamber pace maker functioning in VVIR mode (Figure 2) was implanted successfully under the fascia of the recti abdominis with epicardial, steroid eluting leads tunneled and connected to the device. Both a bipolar and a monopolar lead was implanted (Figure 3) in order to provide potential backup in case a lead would get fractured because of excessive activity of the child. The post-operative course was uneventful, without complications and the child was discharged 7 days after the implantation in very good clinical conditions with the pace maker programmed at a minimal heart rate of 75 b/min according to the physiological needs of a patient of that age.

Discussion

Pacemaker therapy in children involves unique issues regarding patient size, growth, development, and possible presence of congenital heart disease (1). The described implant is the first of its kind to be performed and documented in western and central Africa. Nkoke et al. (2) in Cameroon reported the case of a neonate with complex congenital heart disease with complete atrioventricular block that unfortunately passed away. In Nigeria, Okoroma et al. (3), Namuyonga et al. (4) and Pallangyo et al. (5) respectively described cases with successful outcome with permanent pace maker implantation. Pediatric pacemaker implantation is performed primarily to treat abnormalities of sinoatrial node or atrioventricular node function that lead to an insufficient heart rate. In addition, pacemakers are used (though less commonly) for other disorders, such as congenital long QT syndrome and cardiomyopathy (6-8).

The presence of the Cardiac centre in the area relieves children suffering from such ailments, and other cardiovascular conditions, both congenital and acquired. In the past they most patient had to be evacuated abroad for the procedure to be done in Western countries for selected patients.

The shortage of human resources is a challenge in our country as documented by this case, where the diagnosis of complete atrioventricular block was delayed by 1 year. The lack of neonatologists and pediatricians is contributing to the high mortality associated with of this kind of cardiovascular disease.

Another dominant factor is financial limitation. Even after the problem is diagnosed, it takes often long time before procedures are performed due to lack of financial resources. In our country, similar to many other sub-Saharan countries, the patient and his/her family pays for everything out of pocket. The lack of public health insurance coverage puts in particular poor families at a disadvantage and is a major driver for the childhood mortality.

Transvenous pacemaker implantation in young patients was previously limited by generator size and lead diameter in comparison to vascular dimensions and capacitance (9). Historically, epicardial pacing was more common in children. As technology has improved, generators and leads have become smaller and more advanced, allowing transvenous pacing systems in children, and pacemaker therapy is now possible in neonates. The deciding factor is the weight of the child and the experience of the team. Since the child weighted less than 15 kg, we opted for epicardial pacing with a single chamber system (10,11). The chosen single chamber VVIR pacing mode is an acceptable option in children with structurally normal ventricles, as it requires a single lead and can achieve higher heart rates (12). Use of dual chamber pacemaker requires two leads, and access to the atrium via a limited surgical access may be difficult. Intraoperative and pre-discharge pacer checks were unremarkable with stable parameters.

Conclusions

Epicardial pacing in children is performed with good results in the Cardiac Centre Shisong. The management of these cases is very challenging both for the patients and their families as well as for the medical team. The Cameroonian government and other stake holders should develop strategies to improve access to health care in order to advance the well-being of its citizens, including poor and underserved communities

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jxym.2018.05.04). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices) developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:e1-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nkoke C, Wawo EY, Mfeukeu LK, et al. Complete congenital heart block in a neonate with a complex congenital heart defect in Africa. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2016;6:S78-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okoroma EO, Aghaji MA. Congenital complete heart block: treatment by pacemaker implantation in a 3 month old nigerian child. Cardiologie tropicale 1987;13:167-70.

- Namuyonga J, Lwabi P, Lubega S. Congenital heart block in a ugandan infant. Cardiovasc J Afr 2015;26:28.

- Pallangyo P, Mawenya I, Nicholaus P, et al. Isolated congenital complete heart block in a five-year-old seronegative girl born to a woman seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus: a case report. J Med Case Reports 2016;10:288. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sachweh JS, Vazquez-Jimenez JF, Schöndube FA, et al. Twenty years experience with pediatric pacing: epicardial and transvenous stimulation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2000;17:455-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos N, Rouhollapour A, Kleine P, et al. Long-term follow-up after steroid-eluting epicardial pacemaker implantation in young children: A single centre experience. Europace 2010;12:540-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Czosek RJ, Meganathan K, Anderson JB, et al. Cardiac rhythm devices in the pediatric population: Utilization and complications. Heart Rhythm 2012;9:199-208. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kertesz NJ, Fenrich AL, Friedman RA. Congenital complete atrioventricular block. Tex Heart Inst J 1997;24:301-7. [PubMed]

- Singh HR, Batra AS, Balaji S. Pacing in children. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2013;6:46-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cohen MI, Bush DM, Vetter VL, et al. Permanent epicardial pacing in pediatric patients: Seventeen years of experience and 1200 outpatient visits. Circulation 2001;103:2585-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fortescue EB, Berul CI, Cecchin F, et al. Patient, procedural, and hardware factors associated with pacemaker lead failures in pediatrics and Congenital Heart Disease. Heart Rhythm 2004;1:150-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Cabral TTJ, Charles M, Claude AJ, Flora F, Armel DN, Samuel K. Management of congenital complete atrioventricular block in a 3-year-old boy in natural history in a tertiary centre: a case report. J Xiangya Med 2018;3:23.